Introduction

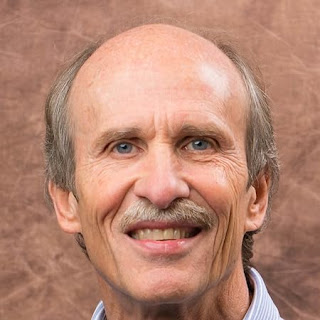

Christopher D. Stanley, Emeritus Professor of Theology at St. Bonaventure University, is one of the leading voices in modern New Testament scholarship. His influential work Arguing with Scripture: The Rhetoric of Quotations in the Letters of Paul plumbs the depths of how Paul uses, adapts, and sometimes reshapes Jewish Scriptures in his epistles. This article explores Stanley’s careful analysis: Did Paul misuse Scripture—or is his method better understood as skilled rhetorical strategy?

1. Background: Stanley’s Major Works

Stanley has written several foundational texts that examine Paul's handling of Scripture:

-

Arguing with Scripture (2004, T&T Clark): focuses on the rhetoric of quotations—how Paul quotes Scripture to persuade different audiences scribd.com+9books.crossmap.com+9bloomsbury.com+9bloomsbury.com.

-

Paul and the Language of Scripture (1992/2008, Cambridge): offers a detailed inventory of Paul’s explicit quotations, and demonstrates his flexible citation techniques cambridge.org+2cambridge.org+2amazon.com+2.

Together, these works form a comprehensive perspective on Paul’s interpretive strategies.

2. Rhetorical Quoting vs. Misuse

Speaker‐Auditor Awareness

Stanley asserts that Paul’s citations are intentional rhetorical devices meant to speak to the thoughts, emotions, and values of diverse first-century audiences books.crossmap.com. Paul quotes Scripture not only once but adapts it depending on the letter’s context—whether addressing a Jewish‐Christian audience or Gentile converts.

Audience Literacy and Reception

Stanley emphasizes that Paul’s audiences varied in their familiarity with Scripture. Some may have recognized entire verses, others only remembered fragments. For them, hearing a line from the Old Testament would trigger emotional resonance, reinforcing Paul’s argument through communal memory cambridge.org+14bloomsbury.com+14fishpond.com.au+14books.crossmap.com+11library.net+1.

3. Quantity and Technique of Quotations

In Paul and the Language of Scripture, Stanley catalogues Paul's explicit quotes across his letters (like Romans, 1–2 Corinthians, Galatians) books.crossmap.com+5cambridge.org+5amazon.com+5. He finds:

-

83 explicit quotations at 74 sites in Paul's letters.

-

Most introduced formally, though not always verbatim—Paul often paraphrases or merges passages, demonstrating interpretive freedom.

-

This pattern holds true in both Jewish and Greco-Roman literature, where authors were expected to reinterpret sources creatively.

4. Examples Where Context Matters

A. Psalm 116 in 2 Corinthians 4

Paul quotes Psalm 116 in a passage about suffering and salvation. Critics argue he lifted it out of its original context. But Stanley counters that Paul’s interpretation aligns with both the LXX and early Christian reception, not an arbitrary misuse amazon.com+2cambridge.org+2cambridge.org+2.

B. Combined Citations

Paul sometimes creates composite citations, merging verses from different texts. While this might seem misleading today, Stanley highlights that it was a common ancient practice meant to weave theological truths from multiple scriptural sources reddit.com+6cambridge.org+6bloomsbury.com+6.

5. Did Paul Misuse Scripture?

Perspective 1: Misuse or Abuse

Some scholars—citing Psalm 116 or other passages—accuse Paul of misusing Scripture by extracting verses for dramatic effect without regard for original meaning. Critics say he bends contexts to fit his agenda .

Perspective 2: Rhetorical Integrity

Stanley challenges the misuse narrative. He argues:

-

Paul expected his audience to share his reverence for the Scripture.

-

His adaptative strategy reflects an ancient interpretive ecosystem.

-

His quotes, even when paraphrased, remain theologically coherent with the textual traditions .

He wraps up in Arguing with Scripture that Paul’s shifts in wording and emphasis are persuasive tools, not deceitful distortions 1library.net+5bloomsbury.com+5fishpond.com.au+5.

6. Audience Reception and Effectiveness

Stanley’s audience‑centered approach focuses on the impact of Paul’s rhetoric. Did it persuade? Did it resonate emotionally and intellectually? He argues yes. Paul’s quotations appear strategically at key argumentative junctures, appealing to a shared spiritual heritage. The effect is not cheap manipulation—it is faithful expansion .

7. Scholarly Reception of Stanley

Reactions to Stanley's work vary:

-

Praise from Dale B. Martin (Yale), Duane Watson (Malone College), and others for his innovative approach and attention to audience mindset amazon.combloomsbury.com+1fishpond.com.au+1.

-

Criticism from some quarters who claim Stanley underestimates the organic theological integrity of Paul's citations—warning against fragmented casuistry cambridge.org+5bloomsbury.com+5fishpond.com.au+5.

Overall, Stanley is viewed as a pioneering voice who challenges simplistic readings of Paul’s intertextual artifice scribd.com+2fishpond.com.au+2bloomsbury.com+2.

8. Implications for Biblical Interpretation

Stanley’s framework has profound consequences:

-

Reading with rhetorical-sensitivity: Encourage attention to why Paul quotes Scripture at particular moments, not just what he quotes.

-

Contextual fluidity: Recognize that Paul, like other ancient writers, felt free to paraphrase or rearrange else.

-

Listeners’ response: Understand interpretive dynamics in communal settings where Scripture was heard, not just read.

These insights help modern readers grasp Paul not as a scriptural contortionist, but as a skillful communicator.

Conclusion: Was Paul Misusing Scripture?

Christopher D. Stanley does not argue that Paul misused Scripture in an unethical way. Rather, he suggests that Paul repurposed Scripture—through paraphrase, citation, and imaginative combination—as a rhetorical instrument tailored to his audience’s memory, identity, and situation.

Where critics may see misquotation, Stanley discerns masterful reinterpretation. The result: Paul emerges not as a manipulator, but as a rhetor trained in persuasive theology—convincing both mind and heart through Scripture shaped to purpose.

For theologians, pastors, and scholars, Stanley’s work is a clarion call: when examining Paul's Scriptures, ask not just what was quoted, but why and how. Misuse or mastery? With Stanley’s lens, we see Paul as neither slippery nor sloppy, but strategic, situational, and deeply faithful to the Scriptures he wove into his gospel witness.